Since 1993

Can a “Match” Really Put You in Prison? The Fingerprint Trap in Florida

By now, you may be aware of my healthy skepticism when it comes to “scientific” evidence. Even top physicists these days claim that matter may not actually exist until we consciously observe it—but a Schrödinger’s Cat discussion is a topic for another day. So, when a lab analyst tells a jury that a defendant’s fingerprints “match” the prints found at a crime scene, we know that the analyst isn’t really saying these prints are from the same person. Rather, they are saying the two sets of prints have a few unique characteristics that match. Retina scans, by comparison, can be far more accurate because our retinas have over 200 unique identifying characteristics, whereas fingerprints have far fewer.

When defending a case involving fingerprints, what happens when the criminal defense attorney decides not to challenge the accuracy of the fingerprint analysis? What then? Here’s a real-life example of just such an instance where an innocent explanation beat a “scientific” match.

Facing Marijuana Grow House Charges in Orlando?

Fingerprint evidence is not an open-and-shut case. The State must prove that the presence of your prints is inconsistent with any innocent explanation. Don’t let circumstantial evidence define your future. Call John Guidry today at (407) 423-1117.

The Legal Breakdown: Cordero-Artigas v. State

In the case of Cordero-Artigas v. State, 75 So.3d 838 (Fla. 2nd DCA 2011), the defendant was convicted of the manufacture of a controlled substance and possession of drug paraphernalia. Basically, he was convicted of owning a “grow house” for marijuana. It was his fingerprints that got him convicted—or so the State thought.

- The Surveillance: The Sarasota Sheriff’s Office had been watching a home for two months, suspecting a grow operation. Cordero was seen on the property, though never entering the actual home, only the garage.

- The Evidence: Inside the home, police found two sheets of paper taped to the wall with fertilization instructions. Two of Cordero’s prints were found on these sheets. Out of over ninety prints found in the house, only these two matched him.

- The Defense: Cordero testified that he had helped a co-defendant bring two air conditioners to the house. He noticed some papers on top of the units, didn’t read them (thinking they were warranties), and moved them. At the time, he never saw any marijuana.

The Power of the “Reasonable Theory of Innocence”

You see where this analysis is going? (Hint: it’s not going well for the State). Circumstantial evidence, like fingerprints, is fine—until a defendant is able to present “exculpatory facts” to rebut it. That’s exactly what Cordero did; he told the jury why his fingerprints were innocently found where they were found.

Once that happened, it became the State’s burden to present evidence that would overcome Cordero’s explanation. The State did not, and Cordero’s conviction was overturned. The court restated the long-standing rule: “circumstantial evidence is insufficient to convict if the State’s evidence does not conflict with the defendant’s reasonable theory of events.”

The Mid-Trial Solution: Motion for Judgment of Acquittal

This whole appeal process could have been averted if the trial judge understood the nature of circumstantial evidence. Unfortunately, some trial court judges seem to shy away from dismissing cases in the middle of trial. A mid-trial dismissal is called a “Motion for Judgment of Acquittal” (JOA).

The appeals court shared my sentiment, writing that a JOA should be granted in a circumstantial evidence case if the State fails to present evidence from which the jury can exclude every reasonable hypothesis except that of guilt. In Cordero’s case, they failed to prove his theory was impossible.

John’s Takeaways

- Fingerprints are Circumstantial: A fingerprint alone only proves you touched an object at some point in time; it does not prove when you touched it or that you were involved in a crime.

- The Rebuttal Rule: If a defendant provides a reasonable, innocent explanation for why their prints are at a scene, the State must produce evidence to disprove that explanation.

- Failure of Proof: If the State “blabs” about a match but can’t provide a “typical script” for how that print got there during the crime, the case should be dismissed.

- The JOA is Critical: A skilled trial attorney must argue for a Judgment of Acquittal the moment the State rests their case to prevent an “insane” jury verdict based on incomplete evidence.

- Local Defense: Whether you are in Orange, Seminole, Osceola, Lake, Brevard, or Volusia County, the standard for circumstantial evidence remains a powerful tool for the defense.

The justice system is harsh, and it is “sad but true” that innocent people get caught up in “grow house” investigations just by being in the wrong place at the wrong time. I have been defending the citizens of Central Florida since 1993, and I know how to turn a “scientific match” back into what it really is: a piece of a puzzle that doesn’t always fit.

Facing these charges? Call John at (407) 423-1117.

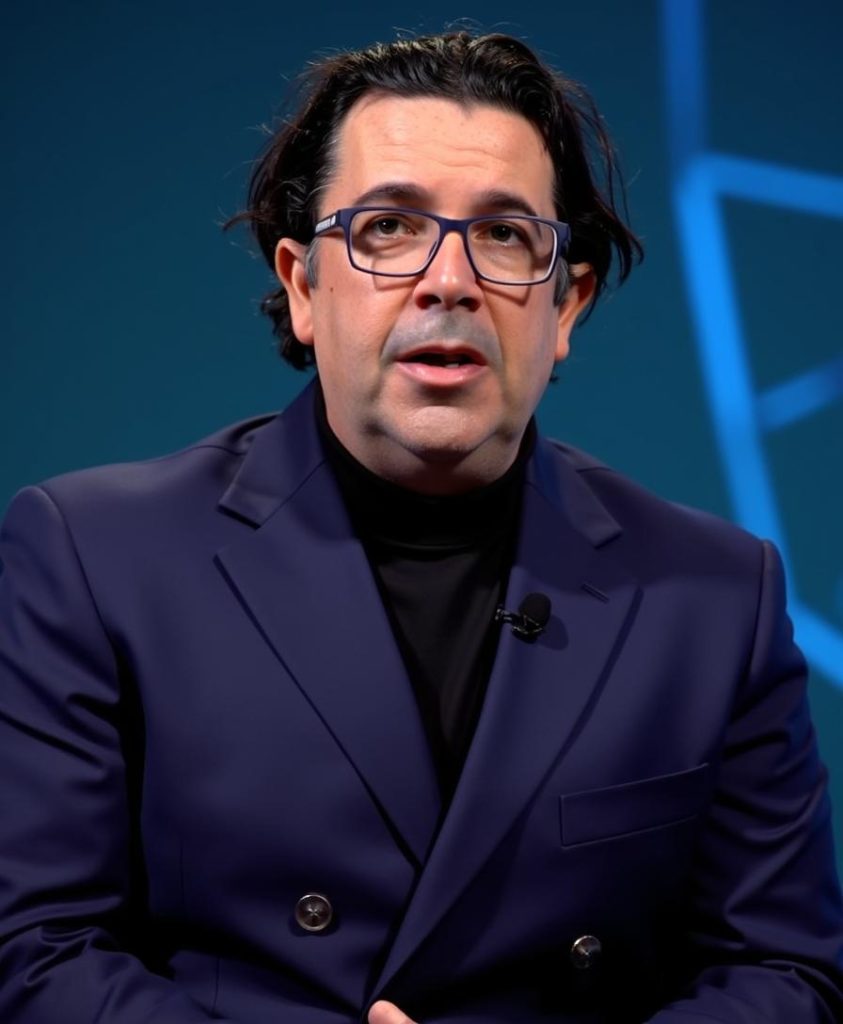

About John Guidry II

John Guidry II is a seasoned criminal defense attorney and founder of the Law Firm of John P. Guidry II, P.A., located in downtown Orlando next to the Orange County Courthouse, where he has practiced for over 30 years. With more than three decades of experience defending clients throughout Central Florida since 1993, Guidry has successfully defended thousands of cases in Orange, Seminole, Osceola, Brevard, Lake, and Volusia counties. He has built a reputation for his strategic approach to criminal defense, focusing on pretrial motions and case dismissals rather than jury trials.

Guidry earned both his Juris Doctorate and Master of Business Administration from St. Louis University in 1993. He is a member of the Florida Bar and the Florida Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. His practice encompasses the full spectrum of Florida state criminal charges, with a particular emphasis on achieving favorable outcomes through thorough pretrial preparation and motion practice.

Beyond the courtroom, Guidry is a prolific legal educator who has authored over 400 articles on criminal defense topics. He shares his legal expertise through his popular YouTube channel, Instagram, and TikTok accounts, where he has built a substantial following of people eager to learn about the law. His educational content breaks down complex legal concepts into accessible information for the general public.

When not practicing law, Guidry enjoys tennis and pickleball, and loves to travel. Drawing from his background as a former recording studio owner and music video producer in the Orlando area, he brings a creative perspective to his legal practice and continues to apply his passion for video production to his educational content.